Gender Equality: Forward or Backward?

Since the early 20th century, Tunisian women played a key role in securing the independence of their country. August 13, 1956, marked the promulgation of the Code of Personal Status (CPS) that included progressive laws aiming at the institution of gender equality.

The Code is known for abolishing polygamy, creating a judicial procedure for divorce, the regulation of family law, marriage, social security, and abortion, among other issues. At the time, it also gave women a status that allows them to create their own businesses, have a bank account and the ability to have their own passports.

The Tunisian woman then, has been portrayed and perceived in the region as independent and emancipated. This image has been well used by both former presidents, constituting a main argument for the country's favorable image in the West, because the suppression of free expression and political opposition tarnished the country's reputation abroad. Under Bourguiba's administration, Tunisia profited from a solid reputation as a civil and secular republic in a region more often comprised of military dictatorships and religiously dependent monarchies.

However, the Code itself was promulgated in an authoritarian manner, as it wasn't the object of public debate, or considered in a constituent assembly. So, the leadership’s reputed modernist conviction masked its democratic deficit. Tunisia is considered as exemplary in advancing women’s rights in the region. However, if you look more closely to the society you may wonder if this image corresponds to reality. Domestic violence, for example is tarnishing the country's shining reputation.

Moreover, the same progressive Code still contains discriminatory provisions that make women “second-class citizens” in their families. For instance, Article 58 of the CPS gives judges the discretion to grant custody to either the mother or the father based on the best interests of the child, but prohibits a mother to have her children live with her if she has remarried. No such restriction applies to fathers.

The Transition

As in many conflicts, women and children are the major victims. During the 2011 Tunisian revolution, women have been subjected to all kinds of violence. A woman’s body has become a threat to her life. Following the overthrown of the former regime, the violence escalated to the kidnapping, raping, trafficking and sexual harassment of girls. Men had even joked about it on Facebook, posting: "The girls that will not be kidnapped today means they're not pretty enough"!

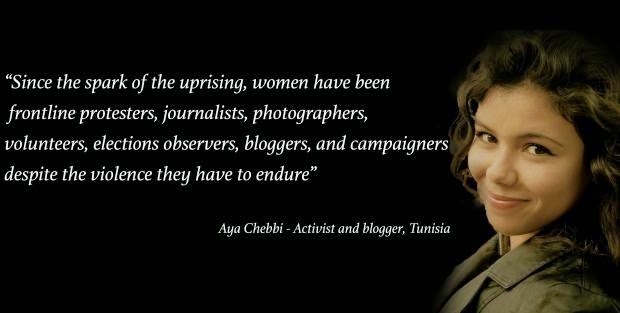

Since the spark of the uprising, women have been frontline protesters, journalists, photographers, volunteers, elections observers, bloggers, and campaigners despite the violence they have to endure. The police, for instance, was taking advantage of the chaos to sexually harass women on account of them being protesters, journalists or detainees. Police might even share their violence to the victim as was the case in September 2012, when a woman had been arrested and charged with public indecency because she had been raped by two police officers! So, Tunisia is still the place where both law and patriotic society would take the side of the perpetrator.

A few weeks after the National Constituent Assembly elections, Souad Abderrahim, the “non-veiled” spokeswoman of the Islamic party Ennahda, said that “single mothers are a disgrace to Tunisians and do not have the right to exist”. She added: “In Arab-Muslim customs and traditions in Tunisia there are no room for full and absolute freedom…”. Such statements eventually paved the way for the rise of Islamic fundamentalism, calling for polygamy and Shariaa Law.

For a country that glows like a beacon of women's progress in North Africa, the government's first shelter for survivors of domestic violence was only inaugurated in December 2012. Tunisia didn’t have one single shelter for women abused, homeless or subjected to violence. Only on 2012 International Day of Women, the provisional interim president Marzouki mentioned the need for the country's first public shelter for victims of domestic violence. Only then, did the Ministry of Women and Family take the first step by bringing the issue of violence against women on board. A few months later, a pilot center, which can only accommodate 50 women and their children, was opened.

On the one hand, Tunisia’s new Constitution, adopted on January 27, has strong protection for women’s rights. Article 46, declares that “The State commits to protect women’s established rights and works to strengthen and develop those rights.” It further guarantees “equality of opportunities between women and men to have access to all levels of responsibility and in all domains” and “guarantees the elimination of all forms of violence against women.” This is an improvement from previous constitutional drafts that invoked notions of “complementary” gender roles that risked diluting the principle of equality between men and women. One of the moments of backwardness was while discussing the issue of "Equality or Complementarity" between men and women after a century of guaranteeing progressive gender equality laws. On the other hand, the new constitution still fails to fully embody the principle of equality between the sexes as it refers to equal opportunity in “assuming responsibilities,” but not to the broader right to equality of opportunity in all political, economic, and other spheres.

Since the spark of the uprising, women have been frontline protesters, journalists, photographers, volunteers, elections observers, bloggers, and campaigners despite the violence they have to endure. The police, for instance, was taking advantage of the chaos to sexually harass women on account of them being protesters, journalists or detainees. Police might even share their violence to the victim as was the case in September 2012, when a woman had been arrested and charged with public indecency because she had been raped by two police officers! So, Tunisia is still the place where both law and patriotic society would take the side of the perpetrator.

A few weeks after the National Constituent Assembly elections, Souad Abderrahim, the “non-veiled” spokeswoman of the Islamic party Ennahda, said that “single mothers are a disgrace to Tunisians and do not have the right to exist”. She added: “In Arab-Muslim customs and traditions in Tunisia there are no room for full and absolute freedom…”. Such statements eventually paved the way for the rise of Islamic fundamentalism, calling for polygamy and Shariaa Law.

For a country that glows like a beacon of women's progress in North Africa, the government's first shelter for survivors of domestic violence was only inaugurated in December 2012. Tunisia didn’t have one single shelter for women abused, homeless or subjected to violence. Only on 2012 International Day of Women, the provisional interim president Marzouki mentioned the need for the country's first public shelter for victims of domestic violence. Only then, did the Ministry of Women and Family take the first step by bringing the issue of violence against women on board. A few months later, a pilot center, which can only accommodate 50 women and their children, was opened.

On the one hand, Tunisia’s new Constitution, adopted on January 27, has strong protection for women’s rights. Article 46, declares that “The State commits to protect women’s established rights and works to strengthen and develop those rights.” It further guarantees “equality of opportunities between women and men to have access to all levels of responsibility and in all domains” and “guarantees the elimination of all forms of violence against women.” This is an improvement from previous constitutional drafts that invoked notions of “complementary” gender roles that risked diluting the principle of equality between men and women. One of the moments of backwardness was while discussing the issue of "Equality or Complementarity" between men and women after a century of guaranteeing progressive gender equality laws. On the other hand, the new constitution still fails to fully embody the principle of equality between the sexes as it refers to equal opportunity in “assuming responsibilities,” but not to the broader right to equality of opportunity in all political, economic, and other spheres.

Looking forward

The CPS, in many cases, has been used by the male counterpart as a “perfect and complete” paper although it dates back to the independence days! Women’s rights should not only be guaranteed by the CPS but also by the right to education, security, health and employment. The notion of “the most progressive” code in the region doesn’t reflect the reality when it’s lagging far behind neighboring Morocco that has tens of shelters for women, while Tunisia is struggling to sustainably establish its first shelter.

Only in last April Tunisia officially lifted all of its specific reservations to the Convention on the Elimination of All Forms of Discrimination against Women (CEDAW), which is an important step toward realizing gender equality. The government should next ensure that all domestic laws conform to international standards and eliminate all forms of discrimination against women.

Tunisia is also one of a handful of members of the African Union that did not sign, let alone ratify, the Protocol to the African Charter on Human and People’s Rights on the Rights of Women in Africa (Maputo Protocol), which sets out additional rights to CEDAW. To ensure that it continues this leadership on gender equality, Tunisia should also sign and ratify the Maputo Protocol.

Finally, both women and men have to protect women and help them understand that they are born with compromised rights and freedoms. When we talk about gender equality, we usually talk exclusively about women and we forget that gender includes men and women. Gender-based violence, for instance, is mainly about empowering women and exclude the essential contribution of men as perpetrators of violence in most cases. Engaging in creating male awareness of gender issues can let men question their involvement in the problem and in doing so, bring about gender equality.

Only in last April Tunisia officially lifted all of its specific reservations to the Convention on the Elimination of All Forms of Discrimination against Women (CEDAW), which is an important step toward realizing gender equality. The government should next ensure that all domestic laws conform to international standards and eliminate all forms of discrimination against women.

Tunisia is also one of a handful of members of the African Union that did not sign, let alone ratify, the Protocol to the African Charter on Human and People’s Rights on the Rights of Women in Africa (Maputo Protocol), which sets out additional rights to CEDAW. To ensure that it continues this leadership on gender equality, Tunisia should also sign and ratify the Maputo Protocol.

Finally, both women and men have to protect women and help them understand that they are born with compromised rights and freedoms. When we talk about gender equality, we usually talk exclusively about women and we forget that gender includes men and women. Gender-based violence, for instance, is mainly about empowering women and exclude the essential contribution of men as perpetrators of violence in most cases. Engaging in creating male awareness of gender issues can let men question their involvement in the problem and in doing so, bring about gender equality.

Comments

wightmagicmaster@gmail.com

.com Îl poți și Whatsapp:

+17168691327